Application notes

Evaluation of the effect of temperature on fibrillation with powder packing dynamic characterization

In this work, we present how the level of fibrillation can be quantified in a powder blend for cathode with tapped density measurement, and how it evolves with temperature using the GranuPack instrument.

In collaboration with

Introduction

Dry-processes have become more and more popular for electrode production due to their great advantages compared to slurry-based processes. The production cost, in money and carbon footprint, is highly reduced because the drying step, known to consume a lot of energy and time, is simply removed. The material is directly handled in powder form, in dry conditions. Such advantages are however counterbalanced by new challenges to overcome. Indeed, powder handling is generally challenging due to complex and not easy-to-predict behaviours making the process optimization hard. For instance, the bulk density is an important parameter to control since a large bulk density for the powder material results in a high energy density for the electrode due to a high content of active material. At the same time, the flowability of the powder must be good enough to allow the processability of the powder.

One of the most developed dry-process is dry-coating based on direct calendering of a powder material. For this process, the powder must exhibit a plasticizing behavior to transform the granular material into a free-standing film with adequate consistency. This consistency is crucial to be able to paste the produced film on a current collector. For having such plasticizing behavior, Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is a popular binder added to the active material and conductive additive. The PTFE is a polymer with long chains that are naturally agglomerated in their initial form. To activate the plasticizing behaviour, PTFE needs to be fibrillated by kneading and shearing. This transforms the PTFE agglomerates into long fibrils, that tangle PTFE with the other particles (active material and carbon black) ensuring the stability of the free-standing film. The quality and the feasibility of such a film highly depend on the level of fibrillation of the powder blend, influencing also the performances of the electrode and thus of the battery. On the one hand, it is impossible to obtain a free-standing film with a powder poorly fibrillated. On the other hand, a powder too much fibrillated will result in poor flowability, detrimental for handling until the calender gap, and a low bulk density which can lead to a low energy density for the electrode.

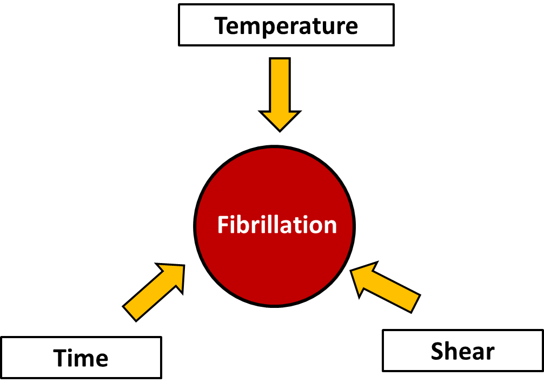

To be efficient, fibrillation needs shearing, temperature and should be processed for a sufficient time, as illustrated in Figure 1. Increasing one or several of these control parameters increases the fibrillation of PTFE. For the specific case of temperature, PTFE should be at a temperature larger than 19°C otherwise the fibrillation cannot occur due to the crystalized polymer chains. The larger the temperature the larger the fibrillation. However, it is hard to predict the speed of fibrillation according to temperature while the level of fibrillation of the resulting powder batch highly influences the properties of the free-standing film. Therefore, it is of huge importance to measure the effect of temperature on fibrillation.

Figure 1: Illustration of the three parameters influencing fibrillation

In this work, we present how the level of fibrillation can be quantified in a powder blend for cathode with tapped density measurement, and how it evolves with temperature. A special focus is paid for the packing dynamic measured by the GranuPack, allowing to quantitatively characterize fibrillation and the effect of temperature on it.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE GRANUPACK

Powder materials

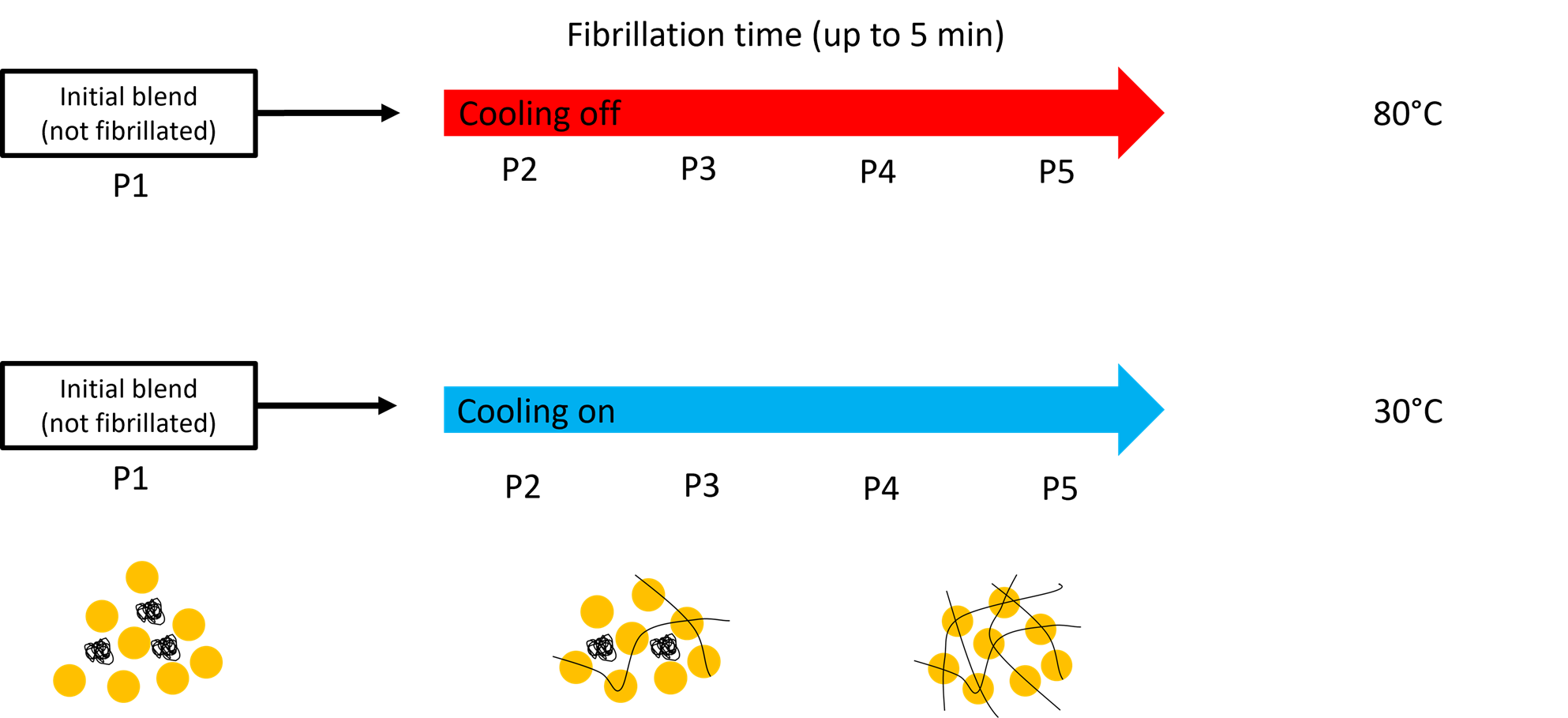

In this work, 9 powder samples were analyzed. The first, named P1 corresponds to the blend of active material, conductive additive, and PTFE not fibrillated. Therefore it can be considered as a batch with 0 min of time of fibrillation. All the batches are made of a majority of Lithium Iron Phosphate (IBUvolt® LFP400) as an active material, some carbon black as a conductive additive, and a minority of PTFE (Daikin Chemical Europe GmbH). Four different times of fibrillation were used to produce batches named P2, P3, P4, and P5 from the lowest to the largest time of fibrillation (up to 5 min). The same times of fibrillation were used to produce two series of powders P2, P3, P4, and P5 at two different temperatures during fibrillation: 30°C or 80°C as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Batches production at two different temperatures for different times of fibrillation.

The powder blends were mixed and fibrillated with an Eirich mixer (5L). The LFP and the carbon black were first mixed to produce a big batch. The friction encountered during mixing resulted in an increase of temperature up to 80°C. Then the PTFE was added and mixed at a very low shear rate to avoid fibrillation. After mixing, some powder was sampled to obtain the powder P1. Then, the fibrillation started and the different powders P2, P3, P4, and P5 were sampled from the big batch at different times of fibrillation. For the series of samples made at a high temperature, the friction generated by fibrillation kept the powder at 80°C. For the series of samples done at a cool temperature, the cooling system of the Eirich mixer was used, allowing a temperature control at 30°C.

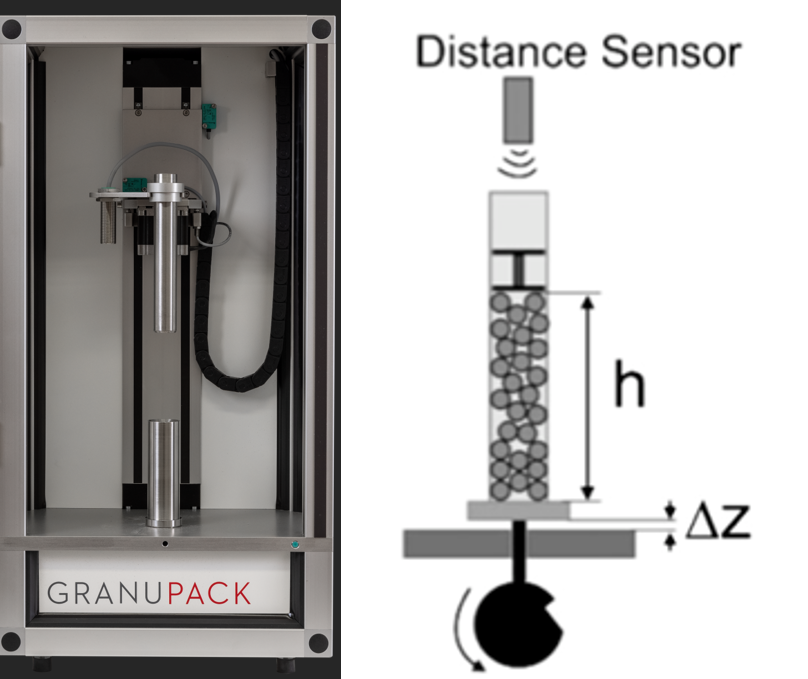

Packing analysis

In this work, we used the GranuPack (see Figure 3) to measure the packing dynamic. Indeed, contrary to other tapped density methods, this instrument allows to measure the complete packing curve of a powder, during the densification, from which the packing dynamic can be computed. The powder is poured into a metallic tube with a rigorous automated initialization protocol. Afterwards, a light hollow cylinder is placed on the top of the powder bed to keep the powder/air interface flat during the compaction process. The tube containing the powder sample rises up to a fixed height of ΔZ and performs free falls. The height h of the powder bed is measured automatically after each tap. From the height h, the volume V of the pile is computed. As the powder mass m is known, the density ρ(n) is evaluated and plotted after each tap n. From the packing curve provided by the GranuPack, the dynamic parameter α is computed. The initial densification speed α is computed with a linear curve adjustment ρ(n) = ρ(0) + α.n on the initial linear part of the packing curve.

Figure 3: (left) Picture of the GranuPack. (right) Sketch of the GranuPack.

For each experiment with the GranuPack, 500 taps were applied to the sample with a tap frequency of 1Hz and 1 mm of free-fall. Measurements were repeated three times for evaluating reproducibility and the average value and standard deviation were considered.

Results and discussion

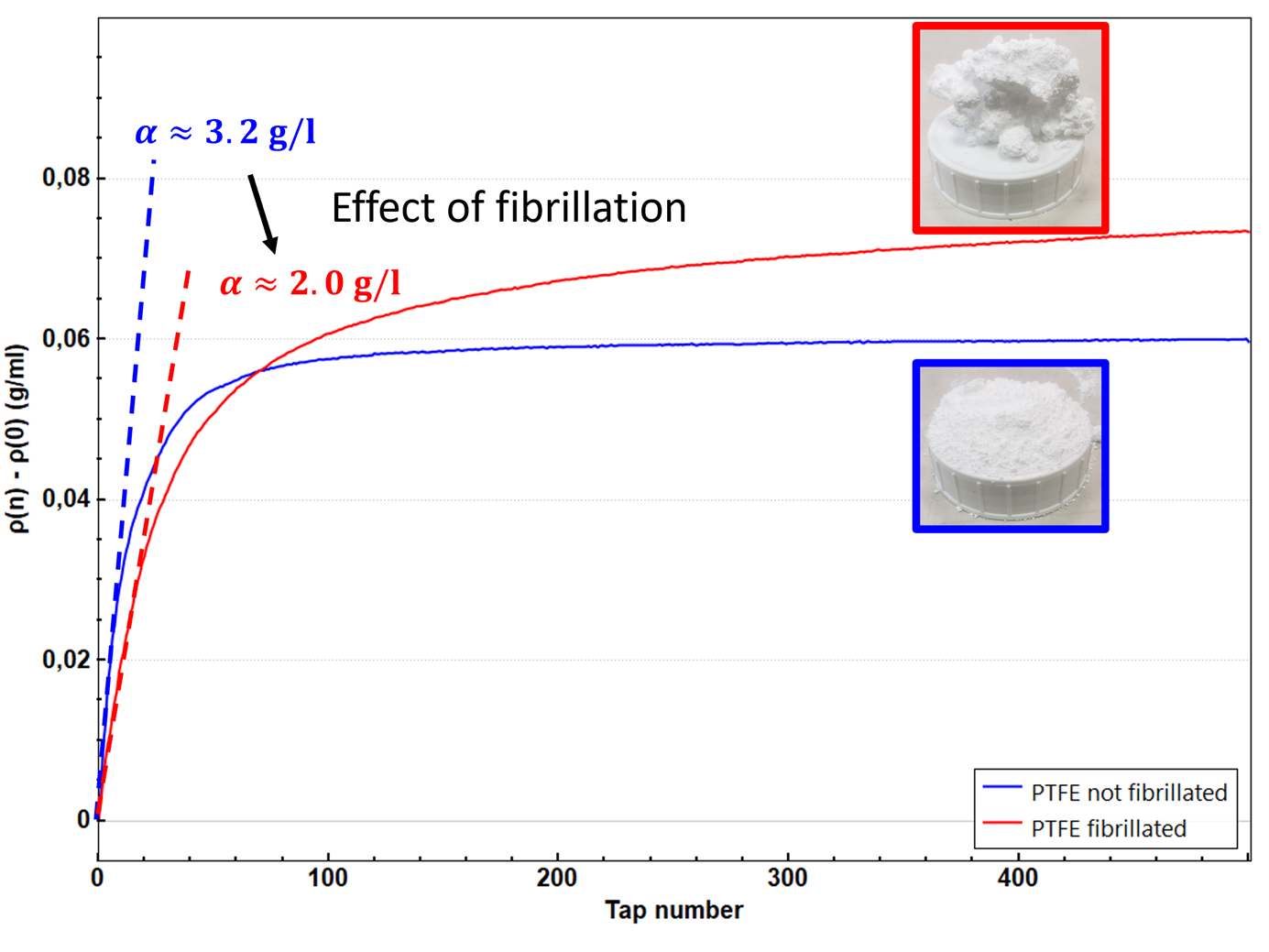

The level of fibrillation can be characterized by the packing dynamic α as seen in Figure 4. Indeed, the more fibrillated PTFE, the longer and more numerous the fibrils of PTFE. As a consequence, the entanglement of particles increases since the PTFE fibrils create a network decreasing the mobility of particles. Therefore, α decreases accordingly since it is proportional to particle mobility.

Figure 4: Effect of fibrillation on α for pure PTFE

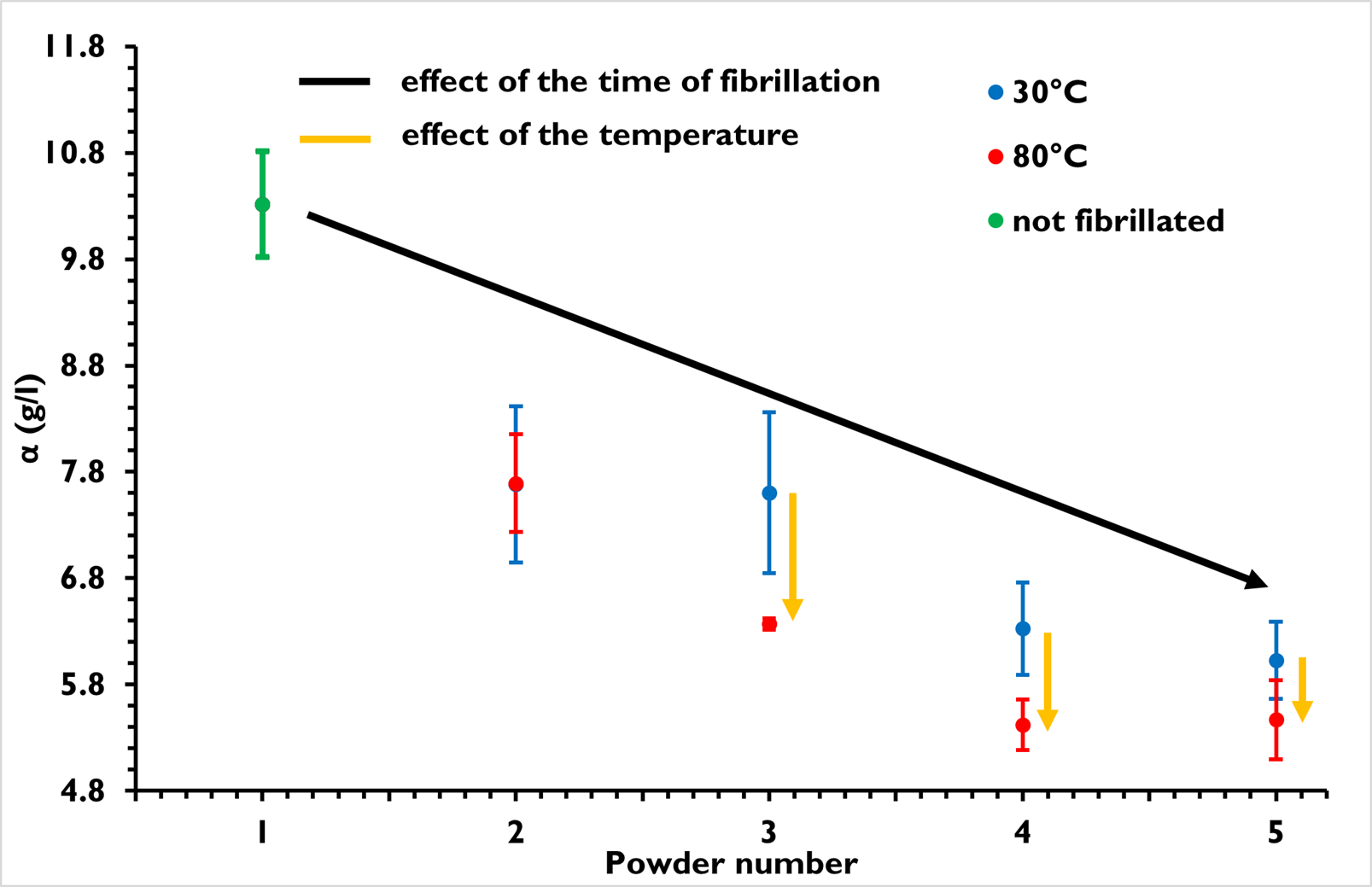

The same effect can be seen with the blends made of active material, conductive additive, and PTFE. In Figure 5, the evolution of α with the time of fibrillation can be seen for 30°C and 80°C. The longer the time of fibrillation the more fibrillated the powder. The network of PTFE fibrils decreases the mobility of the different particles of PTFE, active material, and conductive additive, decreasing their mobility. Therefore, α decreases as the time of fibrillation increases. Nevertheless, the efficiency of fibrillation also depends on temperature, and the larger the temperature the more efficient the fibrillation. Indeed, the softness of the PTFE chains increases as temperature increases, increasing the fibrillation speed. This increase is measured by α as it can be seen in Figure 5. Indeed, for identical times of fibrillation, α is lower at 80°C than at 30°C, attesting to a larger level of fibrillation. For the case of P2 powders, the time of fibrillation is probably too short to obtain a difference due to temperature. However, for longer times of fibrillation, the difference in α is significant between 30°C and 80°C, and the effect of temperature on the level of fibrillation can be quantified by the packing dynamic α.

Figure 5: Evolution of α with the time of fibrillation for samples fibrillated at 30°C and 80°C

Conclusion

In battery manufacturing, the quantification of PTFE fibrillation is an important challenge to solve because the manufacturing process and the performances of the produced battery depend on the level of fibrillation of the powder blend made of active material, conductive additive, and PTFE. The fibrillation depends on three main parameters: the time of fibrillation, the temperature, and the shear rate. Therefore, it is important to have control of these parameters during fibrillation and to assess the effect of these parameters on the level of fibrillation.

Here, we used the GranuPack to measure the effect of temperature on fibrillation and to quantify the level of fibrillation according to temperature and the time of fibrillation. The packing densities of powders fibrillated during different times of fibrillation and at different temperatures were characterized with this instrument. Contrary to existing standardized tapped procedures which only measure initial and final bulk densities after tapping, the GranuPack measures the bulk density of a powder after each tap, giving access to the packing dynamic of the powder. This measure is performed with an automated protocol, reducing the variability coming from the operator, allowing to measure the initial densification speed α in an accurate and repeatable way. This metric measured by the GranuPack demonstrated an adequate quantification of the level of fibrillation. The larger the level of fibrillation the lower α. Therefore, the evolution of fibrillation depending on the time of fibrillation and the temperature can be assessed, opening the way to an optimization of fibrillation for dry process improvement